Hamlet, a cornerstone of English literature, explores complex themes like revenge, mortality, and deception. This guide illuminates the play’s rich symbolism and enduring relevance.

Understanding the Play’s Context

Hamlet’s enduring power stems from its deep engagement with universal human experiences, but appreciating its nuances requires understanding its historical and literary backdrop. Written during the Elizabethan era, the play reflects anxieties surrounding succession, political intrigue, and religious upheaval. Shakespeare masterfully blends elements of revenge tragedy, a popular genre at the time, with profound philosophical inquiries into morality and existence.

The play’s exploration of uncertainty, particularly regarding the ghost’s authenticity, resonates with the era’s shifting beliefs. Furthermore, the subtle motif of incest and the pervasive symbolism of poison and decay contribute to the play’s unsettling atmosphere, mirroring anxieties about corruption and societal breakdown prevalent in Elizabethan England.

Historical and Literary Background

Hamlet emerged from Elizabethan England’s theatrical traditions and reflects the era’s fascination with revenge tragedies, philosophical inquiry, and political instability.

Elizabethan Era and Shakespearean Tragedy

Hamlet was conceived during the vibrant, yet tumultuous, Elizabethan Era (1558-1603), a period marked by significant cultural and political shifts. Shakespeare’s tragedies, including Hamlet, often mirrored the anxieties of the time, exploring themes of power, corruption, and the fragility of human existence.

These plays adhered to specific conventions: a noble protagonist with a tragic flaw, a descent into chaos, and a catastrophic resolution. Revenge tragedy, a popular subgenre, heavily influenced Hamlet, featuring ghosts, scheming villains, and a protagonist driven by vengeance. The era’s belief in ghosts as potentially malevolent spirits adds another layer of complexity to the play’s central conflict, fueling uncertainty and moral dilemmas.

Sources and Influences on Hamlet

Shakespeare didn’t invent the story of Hamlet entirely; he drew upon earlier sources, most notably the 12th-century “Historia Danica” by Saxo Grammaticus. This tale, featuring a prince feigning madness to avenge his father’s murder, provided the foundational plot.

Furthermore, a lost play known as the “Ur-Hamlet,” possibly by Thomas Kyd, circulated in the late 1580s and likely influenced Shakespeare’s work. Renaissance philosophical ideas, particularly skepticism and humanism, also permeate the play, contributing to Hamlet’s introspective nature and questioning of morality. The exploration of revenge, a common dramatic trope, is refined through Shakespeare’s masterful characterization and poetic language.

Key Characters in Hamlet

Hamlet’s drama revolves around Prince Hamlet, his uncle Claudius, Queen Gertrude, and Polonius, alongside Ophelia and Laertes, each driving the tragic narrative.

Hamlet, Prince of Denmark

Hamlet, the protagonist, is a deeply contemplative and melancholic prince grappling with his father’s death and his mother’s hasty marriage to his uncle, Claudius. He’s tasked by his father’s ghost to avenge his murder, a burden that fuels his famous indecision and feigned madness.

His intellectual nature leads to prolonged introspection, famously exemplified in the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, where he contemplates life, death, and the uncertainties beyond. Hamlet’s obsession with uncovering the truth and his moral struggles define his character, making him one of literature’s most complex and enduring figures. He embodies the conflict between thought and action.

Claudius, the Usurping King

Claudius is the play’s antagonist, a shrewd and calculating man who seized the throne by murdering his brother, the former King Hamlet. He presents a façade of regal authority and concern for Denmark, yet harbors a deep guilt and fear of exposure. His actions set the entire tragedy in motion, creating a web of deceit and corruption.

Claudius’s attempts to maintain power involve manipulation, spying, and ultimately, plotting against Hamlet himself. He represents ambition and the corrupting influence of power. Despite his villainy, Claudius is portrayed with a degree of complexity, revealing a man tormented by his conscience, yet unwilling to relinquish his ill-gotten gains.

Gertrude, the Queen

Gertrude, Hamlet’s mother, is a figure of considerable ambiguity. Her hasty marriage to Claudius following her husband’s death deeply troubles her son and fuels his sense of betrayal. While seemingly motivated by a desire for stability and status, her actions are open to interpretation.

Gertrude appears largely passive, caught between her son’s anguish and her husband’s schemes. Her loyalty is divided, and her understanding of the full extent of Claudius’s treachery remains unclear throughout much of the play. She embodies the complexities of female agency within the constraints of Elizabethan society, and her ultimate fate is tragic.

Polonius, Ophelia, and Laertes

Polonius, the Lord Chamberlain, embodies manipulative political maneuvering and verbose advice. His attempts to uncover the source of Hamlet’s madness ironically contribute to the tragedy. His children, Ophelia and Laertes, are deeply affected by his death and the unfolding events at Elsinore.

Ophelia, obedient and vulnerable, is torn between her love for Hamlet and her duty to her father and brother. Her descent into madness, symbolized by her distribution of flowers, is heartbreaking. Laertes, fiercely protective of his sister’s honor, seeks revenge for both Polonius and Ophelia’s deaths, becoming a pawn in Claudius’s plot.

Major Themes in Hamlet

Hamlet grapples with profound themes: action versus inaction, mental illness, deception, revenge’s futility, and the inevitability of mortality—all interwoven throughout the play.

Action Versus Inaction

Hamlet’s central conflict revolves around the paralyzing tension between thought and action. The prince is tasked with avenging his father’s murder, yet he’s plagued by indecision and philosophical contemplation. This hesitation isn’t simply cowardice; it stems from a deep moral and intellectual complexity. He questions the certainty of the ghost’s revelation and fears the consequences of rash action.

This internal struggle fuels the play’s dramatic tension. Hamlet’s famous soliloquies reveal a mind wrestling with existential questions, delaying decisive action. The contrast between his intellectualizing and the decisive actions of characters like Laertes and Fortinbras highlights this core theme, demonstrating the devastating effects of prolonged inaction.

The Complexity of Mental Illness

Hamlet offers a nuanced, though historically-situated, portrayal of mental distress. While not using modern diagnostic terms, the play vividly depicts symptoms consistent with depression and potentially other mental health conditions. Hamlet’s grief over his father’s death, coupled with his mother’s hasty remarriage and the revelation of his uncle’s treachery, triggers a profound psychological unraveling.

His erratic behavior, melancholic soliloquies, and feigned madness raise questions about the nature of his sanity. Is his “antic disposition” a calculated strategy, or a genuine descent into mental instability? The play doesn’t offer easy answers, instead presenting a complex and unsettling exploration of the human psyche under extreme duress.

The Danger of Deception and Manipulation

Hamlet is riddled with deceit, where characters consistently employ manipulation to achieve their goals. Claudius’s regicide and subsequent marriage are built on a foundation of lies, setting the play’s treacherous tone. Polonius, a master manipulator, uses Ophelia as a pawn to uncover Hamlet’s affections and discern the cause of his “madness.”

Even Hamlet himself engages in deception, feigning insanity to investigate Claudius’s guilt. This pervasive atmosphere of distrust erodes genuine connection and fuels the tragedy. The play demonstrates how easily truth can be obscured, and the devastating consequences that arise when individuals are exploited through calculated manipulation and hidden agendas.

The Futility of Revenge

Hamlet grapples intensely with the concept of revenge, spurred by his father’s ghost’s demand for retribution. However, the play ultimately portrays revenge as a destructive and ultimately pointless cycle. Hamlet’s prolonged contemplation and moral hesitation delay action, leading to a cascade of unintended deaths.

The final scene is a bloodbath, demonstrating that revenge doesn’t bring closure or justice, but rather amplifies loss and suffering. Characters seeking vengeance – Hamlet, Laertes, and even Fortinbras – achieve their aims at a tremendous cost, highlighting the futility of pursuing retribution. The play suggests that breaking the cycle of violence is preferable to perpetuating it.

Mortality and Decay

Hamlet is permeated with a preoccupation with death, decay, and the ephemeral nature of life. This theme manifests in numerous ways, from the literal presence of Yorick’s skull in the graveyard scene to the pervasive imagery of disease and corruption within the Danish court.

The play explores not only the physical decay of the body but also the moral and spiritual rot afflicting Denmark. Hamlet’s famous “To be or not to be” soliloquy directly confronts the question of existence and the appeal of oblivion. The constant reminders of mortality force characters – and the audience – to contemplate the meaning of life and the inevitability of death.

Recurring Motifs in Hamlet

Hamlet utilizes potent motifs—poison, incest, ghosts, and disease—to amplify central themes, creating layers of meaning and foreshadowing tragic events within the narrative.

Poison as a Symbol

Poison permeates Hamlet, functioning as a powerful symbol of corruption, both moral and physical. It’s not merely a method of murder, but represents the insidious nature of deceit and ambition that infects the Danish court. The literal poison—in Claudius’s ear and the final duel—mirrors the metaphorical poisoning of the state through regicide and incest.

This motif extends beyond physical harm, signifying the decay of trust and the contamination of relationships. Hamlet’s obsession with uncovering the “rotten” state of Denmark directly connects to this pervasive imagery. The play suggests that poison isn’t just a tool, but a reflection of a deeply diseased society, where appearances mask a core of corruption and betrayal.

Incest and Incestuous Desire

The motif of incest in Hamlet is unsettling and deeply ingrained, representing a profound moral and societal corruption. Hamlet fixates on his mother Gertrude’s hasty marriage to his uncle Claudius, perceiving it as an incestuous act – a violation of natural order and familial bonds. The ghost reinforces this disgust, fueling Hamlet’s rage and contributing to his melancholic state.

This isn’t necessarily literal incest, but rather a symbolic representation of a deeply disturbed family dynamic and a betrayal of proper relationships. The play suggests that this “incestuous” union has poisoned the state, mirroring the corruption at its core. Hamlet’s preoccupation with his mother’s sexuality and the perceived impropriety of the marriage drives much of the play’s conflict.

The Ghost and Uncertainty

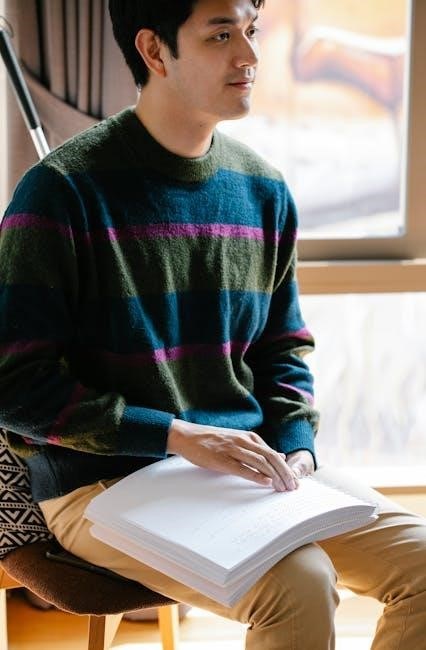

The appearance of the Ghost of Hamlet’s father is pivotal, yet immediately introduces a theme of profound uncertainty. In Elizabethan times, ghosts were ambiguous figures – potentially benevolent, malevolent, or even demonic illusions. This ambiguity permeates the play, as Hamlet grapples with the Ghost’s veracity and the implications of its command for revenge.

The Ghost’s revelation sets the plot in motion, but also casts doubt on everything Hamlet believes. Is it a genuine spirit seeking justice, or a devilish entity manipulating him? This uncertainty fuels Hamlet’s delay and internal conflict, as he seeks proof before acting on the Ghost’s word. The play constantly questions the nature of reality and the reliability of perception.

Disease and Corruption

Throughout Hamlet, imagery of disease and decay pervades the atmosphere, reflecting a deeper moral and political corruption within Denmark. This isn’t merely physical illness; it’s a metaphor for the rotten state of the kingdom following King Hamlet’s murder and Claudius’s usurpation of the throne. The phrase “something is rotten in the state of Denmark” encapsulates this pervasive sense of moral decay.

This motif extends to characters’ behaviors and relationships, highlighting the poisonous effects of ambition, betrayal, and revenge. The literal use of poison – in the murder of King Hamlet and later in the final scene – symbolizes this corruption. The play suggests that this internal rot ultimately leads to the kingdom’s downfall.

Analyzing Key Scenes

Examining pivotal moments—the ghost’s revelation, the “To be or not to be” soliloquy, the play-within-a-play, and the graveyard scene—unlocks Hamlet’s core themes.

The Ghost’s Revelation (Act I, Scene V)

This scene is foundational, as the Ghost of Hamlet’s father reveals the truth of his murder by Claudius, igniting the play’s central conflict. The Ghost demands revenge, burdening Hamlet with a task that fuels his internal struggle.

The revelation introduces the motif of uncertainty; is the Ghost trustworthy, or a deceptive spirit? Elizabethan audiences believed ghosts could be benevolent or malicious, adding layers of complexity. Hamlet’s subsequent feigned madness stems directly from this encounter and the weighty command for retribution.

Analyzing the Ghost’s language and the atmosphere Shakespeare creates is crucial. The scene establishes themes of corruption, betrayal, and the moral decay within the Danish court, setting the stage for the tragedy to unfold. It’s a pivotal moment of dramatic irony.

The “To Be or Not To Be” Soliloquy (Act III, Scene I)

Perhaps the most famous passage in English literature, this soliloquy isn’t simply about suicide; it’s a profound meditation on life, death, and the unknown. Hamlet contemplates the pain and injustice of existence, weighing them against the fear of what comes after death.

He grapples with the moral implications of action versus inaction, questioning whether enduring suffering is nobler than taking arms against it. The “undiscovered country” represents the terrifying uncertainty of the afterlife, paralyzing him with doubt.

Understanding the context – Hamlet is being spied upon – adds another layer. It’s a moment of raw vulnerability, revealing his inner turmoil and contributing to the play’s exploration of mental illness.

The Play Within a Play (Act III, Scene II)

Known as “The Mousetrap,” this staged performance mirrors the events of King Hamlet’s murder, designed by Hamlet to gauge Claudius’s guilt. It’s a brilliant demonstration of deception and manipulation, a play within a play serving as a psychological experiment.

Hamlet meticulously observes Claudius’s reaction, seeking confirmation of his uncle’s crime. The king’s visibly disturbed response – abruptly stopping the play – provides the evidence Hamlet desperately needs, solidifying his suspicions.

This scene highlights the theme of appearance versus reality, as the play exposes the hidden truth beneath a façade of normalcy. It’s a pivotal moment, escalating the conflict and driving the plot forward.

The Graveyard Scene (Act V, Scene I)

This iconic scene, featuring the gravediggers, is a profound meditation on mortality and the inevitability of death. Their seemingly callous banter while digging Ophelia’s grave underscores the leveling power of death – all are reduced to dust.

Hamlet’s contemplation of Yorick’s skull, a former court jester, forces him to confront the physical decay of even those he once knew and loved. It’s a visceral reminder of human transience and the futility of earthly ambition.

The scene dramatically shifts with Ophelia’s funeral, igniting a conflict between Hamlet and Laertes, foreshadowing the tragic climax and highlighting the play’s pervasive sense of loss.

Symbolism in Hamlet

Hamlet masterfully employs symbolism; flowers represent Ophelia’s innocence, skulls signify mortality, and clothing embodies deception, revealing a contrast between appearance and reality.

Flowers and Ophelia

Ophelia’s distribution of flowers in Act IV, Scene V is profoundly symbolic, each bloom carrying a specific meaning reflecting the characters and events of the play. Rosemary, for remembrance, and pansies, for thoughts, are given, highlighting lost connections and fading memories. Violets, traditionally representing faithfulness, are notably absent, signifying the loss of love and loyalty.

Rue, symbolizing repentance, is offered to both Gertrude and herself, acknowledging guilt and regret. Daisies, representing innocence, are also distributed, ironically contrasting with Ophelia’s own compromised state. This poignant scene underscores her descent into madness and serves as a commentary on the corruption and decay within the Danish court, using floral language to express unspoken truths and emotional turmoil.

Skulls and Mortality

The graveyard scene (Act V, Scene I) and the iconic image of Yorick’s skull are central to Hamlet’s contemplation of mortality and the inevitability of death. Holding the skull, Hamlet reflects on the physical decay that awaits all humans, regardless of status or accomplishment. This encounter forces him to confront the futility of earthly ambitions and the transient nature of existence.

The skull serves as a memento mori, a reminder of death, prompting philosophical musings on the afterlife and the meaning of life. It symbolizes the leveling power of death, reducing all individuals to the same state of decomposition. This motif underscores the play’s pervasive preoccupation with decay, corruption, and the fragility of human life.

Clothing and Appearance vs. Reality

Throughout Hamlet, clothing functions as a powerful symbol of deception and the disparity between outward appearance and inner truth. Characters frequently adopt disguises or use clothing to conceal their true intentions, mirroring the play’s broader exploration of hidden motives. Hamlet’s “antic disposition” itself is a form of sartorial and behavioral masking.

Claudius’s regal attire contrasts sharply with his villainous nature, highlighting the deceptive facade he presents to the court. The emphasis on clothing underscores the theme that things are not always as they seem, and that appearances can be deliberately misleading. This motif reinforces the play’s questioning of authenticity and the difficulty of discerning truth.

Critical Approaches to Hamlet

Diverse lenses—Psychoanalytic, Feminist, and New Historicism—offer unique interpretations of Hamlet, revealing its complexities and enduring power through varied critical perspectives;

Psychoanalytic Criticism

Psychoanalytic approaches, heavily influenced by Sigmund Freud, delve into the unconscious motivations driving Hamlet’s actions. Critics explore Oedipal complexes, particularly Hamlet’s conflicted feelings towards his mother, Gertrude, and his uncle, Claudius. The play’s pervasive themes of death, decay, and repressed desires are examined through this lens.

Hamlet’s procrastination isn’t simply indecision, but a manifestation of internal psychological conflicts. His obsession with his mother’s hasty remarriage suggests unresolved feelings and a struggle with sexual identity. Furthermore, the ghost itself can be interpreted as a projection of Hamlet’s own unconscious guilt and anxieties, fueling his quest for revenge and self-destruction. This perspective reveals a deeply troubled psyche at the heart of the tragedy.

Feminist Criticism

Feminist readings of Hamlet challenge traditional interpretations by focusing on the limited agency and societal constraints imposed upon its female characters. Gertrude and Ophelia are often viewed not as simply flawed individuals, but as victims of a patriarchal system that denies them voice and control over their destinies.

Ophelia’s descent into madness is re-examined as a response to the emotional manipulation and betrayal she experiences from Hamlet, Polonius, and her brother, Laertes. Her symbolic association with flowers during her madness highlights her silenced grief and lost innocence. Gertrude, too, is scrutinized for her perceived passivity and quick remarriage, prompting questions about the pressures she faced as a queen in a male-dominated court. These analyses reveal the play’s complex portrayal of female experience.

New Historicism

New Historicism approaches Hamlet by situating the play within its specific historical context – Elizabethan England – and examining its relationship to the cultural, political, and social anxieties of the time. This perspective moves beyond simply viewing the play as a timeless exploration of universal themes.

Instead, it investigates how Elizabethan beliefs about ghosts, succession, disease, and the divine right of kings shape the play’s narrative and characters. The pervasive sense of corruption and decay in Denmark can be linked to contemporary fears about political instability and moral decline. Analyzing the play alongside historical documents—like treatises on witchcraft or political pamphlets—reveals how Shakespeare engaged with and reflected the concerns of his era, offering a nuanced understanding of the play’s original meaning.